|

|

|

Warwick’s Bloomer Girl –

Lydia Sayer Hasbrouck by S. Gardner

|

|

On a fateful day in her young

life, Lydia Sayer applied for admission to the Seward Institute in

Florida. The very intelligent,

attractive, athletic, and independent -minded girl would have been eager to

continue her education. One wonders if it had ever occurred to her that the

practical garments she had adopted at an early age – long before Amelia

Bloomer ever popularized them-- would be a problem. But problem there was, and she never did

attend Seward Institute. She was rejected because she refused to lay aside

what would later be called “bloomers” for more traditional dress. “As I

left…I fairly bathed my soul in an agony of tears and silent prayers,” she

later said, “I registered a vow that I would stand or fall in the battle for

women’s physical, political and educational freedom and equality.” Thereafter

she became one of the most vocal and staunchest supporters of women’s dress

reform and suffrage in America.

|

|

Lydia was born on Dec. 20, 1827 in Sayerville, a hamlet of

Warwick near Bellvale. She was the

daughter of Benjamin Sayer and Rebecca Forshee. As a child she was fearless, self-reliant,

skilled in horsemanship and the domestic arts, and keenly interested in books

and learning. She finished her

education elsewhere-- at Miss Galatian’s Select School, the Elmira High

School, and Central College. Around

1849 she became keenly interested in the health disciplines of hydropathy, or

the ‘water cure’. This social movement

promoted what today would be called a holistic approach to health. Water cure enthusiasts advocated a

vegetarian diet, moderate exercise, sensible clothing, avoidance of alcohol,

and exercise, along with cleansing the patient with a soothing wrap of wet

sheets. Shortly after 1853 Lydia entered the Hygeia-Therapeutic College in

New York City and graduated as a doctor of medicine.

|

|

Dr. Lydia Sayer went to Washington D.C. and practiced there,

lecturing in neighboring cities on the tyranny of fashion. While there she became the Washington

correspondent for the Middletown Whig Press, a paper with liberal and

reformist positions on many issues. She eventually married its owner John

Hasbrouck in a simple common-law ceremony at the Sayer home on July 27, 1856,

less than a month after establishing a reformist newspaper of her own, The

Sibyl. The only concession she made in her wedding garb was that her

bloomer outfit was cut from white cloth.

|

|

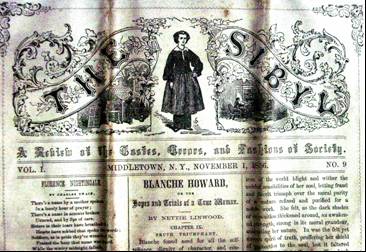

The archive of the Historical Society contains issues of The

Sibyl from 1856 through1863. Here

one finds a wealth of information of interest to progressive minded ladies

and gentlemen of the day:

|

|

“Ever since the agitation of Dress Reform, newspapers,

physicians, and people in general have been convinced that the present style

of dress was blighting to woman’s physical being; yet, with but few

exceptions, none have shown themselves practical reformers….Upon this point

we wish to be understood, in advocating Dress Reform. It is merely as a physiological reform, to

elevate the weakened stamina of the race, and it not to be engrafted in the

woman’s rights movement toward the elective franchise. Though we may sustain them all, yet this

reform is individualized, and of a higher importance than all else; for until

woman is physically freed from her bonds, she is unfitted, in a great

measure, for the active duties of trade, or a profession, or the arena of

political strife...”

|

|

“Most of the ladies who have retained the Reform Dress are wives

and mothers. Many had suffered from

the effects of weight or pressure, until the weakened muscles cried for

release..”

|

|

“…the Abbe de Deguessy observed in a sermon, ‘Women now-a-days

forget, in the astonishing amplitude of their dresses, that the gates of

Heaven are very narrow.’ This recalls

an incident we witnessed the other Sabbath…A great rumpling, smashing and

crushing startled us at the door, and looking around to see what the matter

was, we witnessed a lady, well hoped and spangled, trying to crush the

unwieldy folds, floating in heavy luxuriance over her rotund hoops. At last she succeeded in clearing the

door…She passed on up the borad aisle, filling it completely, and rattling

her hoops and silks against either side.

Reaching the seat, she solved the dilemma of how she was to enter it,

by crushing, and crowding, and folding, until at last she was safely

seated. It struck us as being and

unprofitable task, this laboring so hard to make oneself uncomfortable. Woman has great endurance, truly.”

|

|

--The Sibyl, Vol. 1, No. 2, July 15, 1856

|

|

Dr. Lydia continued her activities on behalf of women’s freedom

on many fronts, as well as dress reform, for her entire life. A glimpse of her personality and tenacity

is seen in this article from the Franklin Repository and Transcript of

Nov. 14, 1860:

|

|

“Mrs. Dr. Lydia Sayer Hasbrouck, of Orange County, New-York, who

insists that a woman should not be taxed unless she is allowed to vote, has

thought to shame the collector out of his deman by offering to work out her

road tax. The doctress, having

somewhat passed the bloom of youth, made no impression upon the stony

official, and therefore, instead of paying under protest, as some of her

sisters do, she went upon the road and drove a cart.”

|

|

She lived most of her adult life with her husband in Middletown;

one cannot but think what she would have been if her family had ‘reined her

in’ at an earlier age—if that was possible—or if the Seward Institute had

turned a blind eye to her eccentric dress.

|